Published July 1, 2021

Published in the Rocket Miner by Hannah Romero

Yufna Soldier Wolf knelt on the ground, scooping out a shallow hole into which she placed a small cast iron skillet filled with sage. Shaleas Harrison, bare toes sinking into the sand, walked over to help shield the skillet from the breeze as Yufna lit a match.

With fragrant smoke rising in front of her, Yufna prayed in Arapaho and then in English to the Creator. She touched the earth, wafted the smoke over herself, and then invited anyone who wanted to receive a blessing to kneel, touch the land, and take in the smoke.

“Once we step outside, we’re back into our church,” Yufna explained.

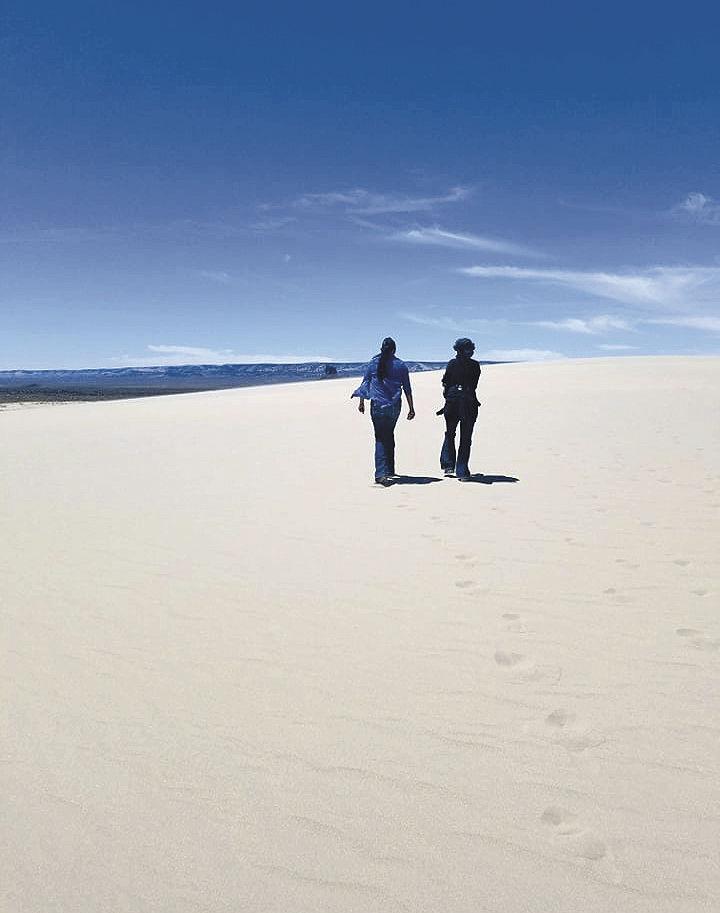

Once the blessing was finished, the small group of roughly a dozen people sat in a circle on the ground, looking across the sagebrush to the Killpecker Sand Dunes and Boar’s Tusk rising in the distance. Then the conversations began.

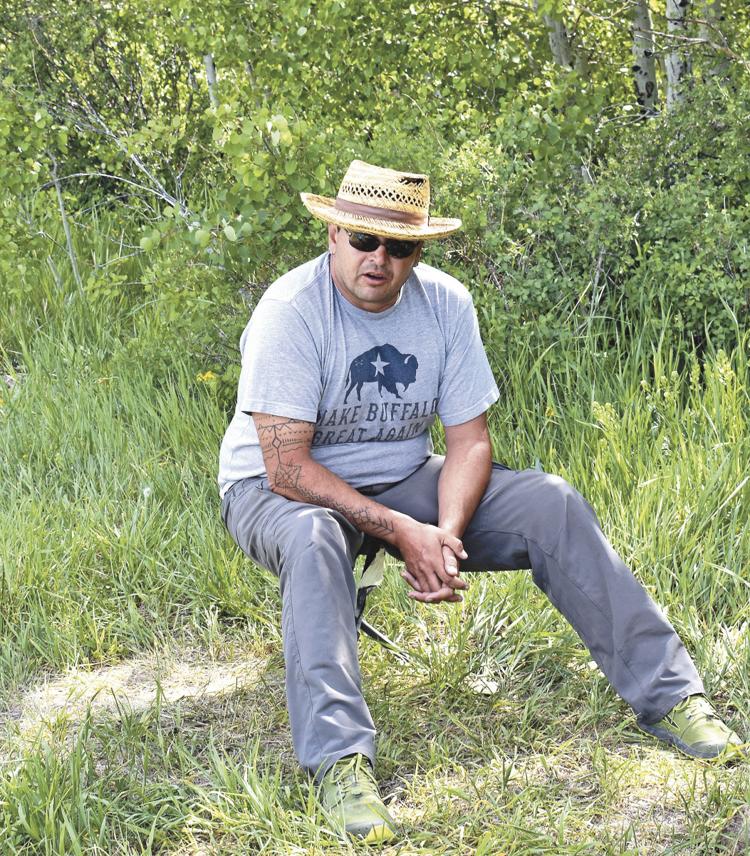

The Boar’s Tusk overlook was the first stop in an all-day tour of the Red Desert, organized by Citizens for the Red Desert and led by tribal advocates Jason Baldes and Yufna Soldier Wolf, Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribal members of the Wind River Nation. The tour also stopped at the White Mountain petroglyphs, the Killpecker Sand Dunes, and Steamboat Mountain.

At each site, our group would gather, usually seated in a circle on the ground, and discuss the land surrounding us — its history, what we can learn from it, and how we can honor and protect it.

Yufna traveled with the group through the day, and Jason met us on Steamboat. They both took the time to share their unique insights and perspectives on the Red Desert, teaching us about the ways their tribes view the land, the significance of certain spots, and how tribal knowledge can work together with conservation efforts.

PRESERVING THE LAND

Conservation through partnership with all the people who claim and use the land is exactly what Citizens for the Red Desert aims for.

The group is described as “a loose coalition of citizens, groups, and interests that value this landscape and want its unique values to endure into the future, free from harmful actions and large scale industrial activities.”

“Our vision is a Red Desert where wildlife thrive, undeveloped lands are connected, traditional and ancestral uses continue, histories are honored, and opportunities for solitude, responsible recreation, and spiritual experiences flourish now and into the future,” Citizens for the Red Desert says.

Shaleas Harrison, the Citizens for the Red Desert Coordinator and a member of the Wyoming Outdoors Council, worked with Yufna and Jason to organize and lead the Red Desert tour, and throughout the day she offered insight into conservation goals for the area.

“The Red Desert is a landscape that deserves permanent protection,” Shaleas said.

One of the major goals Citizens for the Red Desert is working toward is developing a congressional bill to conserve the landscape. Shaleas explained that a bill could provide more diversity to represent different groups and give protection in more specific ways, as opposed to something that only gives a “broad sweeping designation,” such as making the area into a national park.

Shaleas pointed out how badly updates are needed in how the land is managed, noting that the current Environmental Impact Statement regarding the area is from the 1990s. Citizens for the Red Desert also hopes for updates to provide more concrete guarantees for conservation of the landscape.

“For so long there’s been too much uncertainty about the future of this place,” Shaleas said.

The main goal is protecting and preserving the land, according to Shaleas. She said the hope is to prevent the land being slowly chipped away at and damaged until it’s not the same, and to try to protect the places that have retained more wildness and not been as disturbed.

Shaleas’s goal is to work directly with the people who use the land, because she believes that “with a grassroots effort by local citizens, we can have a local solution.”

As part of working with everyone connected to the land, Citizens for the Red Desert especially wants to hear from and include the perspective of the people who’ve been using the land the longest.

Shaleas said she wants to “build a platform for tribal nations” to speak about their ancestral lands that have become a part of all of our lives.

UNDERSTANDING THE HISTORY

The Red Desert includes land claimed by multiple tribes as ancestral land. Tribes that lived on and used the land include the Shoshone, Ute, Goshute, Paiute, Bannock, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Lakota, and Crow. The Red Desert has also been identified as sacred by the Eastern Shoshone, Uintah, Ouray, Arapaho, and other Native peoples.

Yufna explained that it is fairly common for lots of different tribes to have claim to the same land, and that they all have unique perspectives on and connections to the area. Including the narratives of the many tribes who have used the Red Desert is one of Yufna’s main goals. She is working with other tribes, including those now settled in other states, to make them a part of the conservation process and ask them what they want for the land.

With so many tribes using the Red Desert for thousands of years, the area includes multiple ancestral lands and sacred sites. Yufna and Jason offered perspective into the significance of some of these sites to their tribes and others.

As we looked across the land to Boar’s Tusk, Yufna commented that she’s tried to find out where the name “Boar’s Tusk” came from, and has yet to learn the answer. But as a member of the Northern Arapaho, Yufna knows the extinct volcano as “The Parents” or “The Guardians” — a name that reflects the way the structure resembles two people holding a blanket.

While “The Parents” is not one of the most sacred sites for the Arapaho, who migrated to the area, Yufna knows that it is a sacred site to many other tribes who lived in the Red Desert. Many of the tribes that settled in the area, including the Eastern Shoshone, have creation narratives connected to the site.

The petroglyphs that can be found in the Red Desert are other significant sites that show the evolution and history of tribes in the area, according to Yufna. She said that each drawing has a meaning and tells a story. Dwelling sites that feature rock art would not only be used by multiple tribes, but also by multiple generations over time, Yufna explained.

The Killpecker Sand Dunes also have thousands of years of history connected to multiple tribes. The ephemeral pools that appear at the dunes provided a source of water, and the landscape provided a sanctuary. Yufna explained that human remains have been found in the area, which was likely a place where elders who couldn’t go on were taken to live out their last days peacefully.

Steamboat Mountain is a sacred site for the Eastern Shoshone people, Jason explained, and was the site of a buffalo jump used by the tribe.

Tribes used these sites and others for thousands of years, until the land was taken from them. Jason discussed how the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1863 established 44 million acres of land that was meant to be given to the tribes, which included the Red Desert, but later the treaty was reduced by 43 million acres.

Although the land no longer belongs directly to the tribes, it is still used by tribal members. Jason and Yufna explained that many tribes still return to the Red Desert to pray, perform ceremonies, gather plants, find animals, and carry out other practices that have been in place for generations. Both Yufna and Jason expressed their desire for their tribes to be able to continue to reconnect to the land in even more significant ways.

For many tribal members, protecting the Red Desert is a critical part of protecting thousands of years of knowledge and traditions. But Yufna and Jason also believe that thousands of years of knowledge are a crucial part of how the land can be conserved.

USING THE PAST TO SECURE THE FUTURE

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) could be key to the Red Desert’s conservation, according to Yufna and Jason.

“TEK is the evolving knowledge acquired by indigenous and local peoples over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment,” the US Fish and Wildlife Service explains. “This knowledge is specific to a location and includes the relationship between the plants, animals, natural phenomena, landscapes, and timing of events that are used for lifeways.”

TEK relates to “rematriation,” the concept of reconnecting to and reclaiming the land, and is connected to spirituality, culture, knowledge, and resources, according to Citizens for the Red Desert.

Yufna explained that TEK relates to the knowledge that tribes passed down through generations of oral history, and includes the knowledge of why specific sites were used for specific purposes. For example, she pointed out a spot at the petroglyphs where it looked like water may come out. Water brings energy and acts as a portal, Yufna said, and it could be one of the many reasons that tribes used that site.

Jason believes TEK can help us conserve the land now. He pointed to how tribes successfully managed species in the past, including both ungulates and predators. Jason also believes restoring past environments will help — specifically, restoring bison. Having studied bison and worked extensively toward bison conservation and restoration, Jason believes that bison are a keystone species and a foundation of the ecosystem that has been missing but could increase biodiversity if restored.

“We need to think more holistically,” Jason said.

Jason and Yufna described how TEK also connects to the mindset and worldview of the tribes who used the land for generations. Jason explained that the people who used to live in the Red Desert understood natural laws, principles, cycles, polarities, and balance, and how there are consequences when you disrupt the balance. Ceremonies are one way of keeping things in balance.

Yufna demonstrated this concept when visiting the petroglyphs. Before our group approached the site, Yufna and her daughter Blue Moccasin went ahead of us and left a tobacco offering. Yufna told us beforehand that the offering is a way to show that we are here to learn and educate and we want to be respectful.

“What we take away, we need to give back, otherwise the balance will be off,” Yufna said.

Jason also emphasized that “it’s important to give if you’re going to take,” and said that “when we find balance, we find ways to be better.”

While Jason and Yufna believe TEK can help preserve the Red Desert for the future, they also recognize the challenges that come with passing on knowledge.

Yufna expressed her concern over generations losing their culture. Tribal knowledge is something that has to be passed on through the tribes from one generation to the next — not like Google or DIY, Yufna joked. In all seriousness, she pointed out that many tribes lost elders to COVID-19, losing valuable sources of tribal languages and history. Yufna hopes knowledge will continue to be preserved and passed on.

“If we don’t do it now, we’re going to lose it forever,” Yufna said.

Jason also expressed a desire to act quickly when it comes to tribes working together with conservationists to share their knowledge and protect the land.

“What will be here down the road if we don’t change our ways now?” he asked.

Both Jason and Yufna also discussed the difficulty of dealing with the trauma of the past. Yufna explained that many tribes are hesitant to share their knowledge because of what has been taken from them. She discussed how hard it is to see tribal possessions in museums and to try to move people away from the perspective that the tribes are just exhibits that no longer exist.

But Yufna and Jason both have hope for their tribes, and others, to be able to move forward.

“We pass on trauma, but we also pass on how strong we are,” Yufna said. She also said that the past is the past, and the focus should be on what can be done now and the legacy that can be left.

Jason believes the connection to the land is an integral part of the tribes moving forward. He thinks conservation should focus on restoring what has been disrupted and letting nature heal, with the understanding that when “we heal the land, we heal ourselves.”